Mozambique’s Banhine National Park was proclaimed in 1973 to serve as a safe haven for large wildlife populations, which included some of Africa’s more interesting animals, such as giraffe and ostrich. Unfortunately the abundance of wildlife once found here was nearly eradicated during the civil war, which was followed by severe droughts and illegal poaching activities.

The Mozambique government is, however, deeply committed to restoring the country’s conservation areas, which takes up nearly a quarter of its total landscape. It has a long-standing relationship with Peace Parks Foundation and through this, Banhine, along with Limpopo and Zinave national parks as part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, as well as Maputo Special Reserve and Ponto do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve as part of the Lubombo Transfrontier Conservation Area, are all being developed through various management and funding agreements.

Banhine has all the characteristics of a true African wilderness and, as it is still in the early stages of development, life in the park is one of adventure. Peace Parks’ Ernst Beyleveld, who works as the Law Enforcement Operations Manager, spends much of his time exploring the park. “Life in Banhine can be difficult as it is a harsh landscape, especially during the dry season when there is very little water to be found. You must have the right attitude and personality to be able to function in this park. What makes it all worth it, is that you spot something new almost every day, or find a new area abundant with birdlife and animals, much like the early explorers did in the 1800s. The black backed jackals calling at night and the black-headed oriole singing during the day are enough to brighten up anyone’s mood.”

Reconnecting ancient corridors

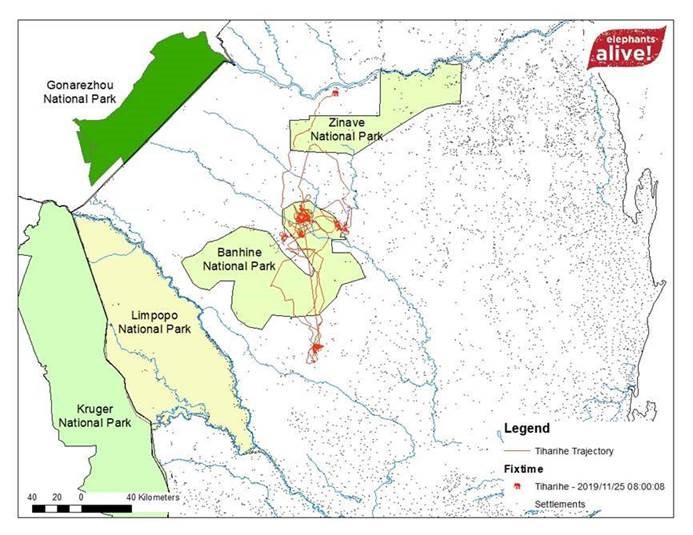

Situated within the Mozambique component of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, Banhine National Park forms the central core of an ancient wildlife corridor that stretches from Kruger National Park in South Africa, across the border through Limpopo National Park and all the way up to Zinave National Park. For centuries large herds, for example, of migratory elephant, have been using this route in their search for water, food and safe breeding grounds.

In 2019, an elephant bull was collared to gain a better understanding of how these large mammals move through the landscape. “The tracking collar showed that in November of that year, the bull travelled across rural areas to Zinave National Park, documenting a new link on the map between the two protected areas. A few days later he moved back down around Banhine’s eastern border, straight to a densely vegetated area south of the Park. He then headed west into Limpopo National Park and all the way into South Africa’s Kruger National Park,” says Peace Parks’ Senior Project Manager, Antony Alexander. “What made this even more interesting was that another elephant bull that had been collared previously also travelled a similar route a year earlier. This is significant evidence of ancient connectivity between these parks.”

The free movement of wildlife does, however, bring about significant challenges. “Communities living in and around Banhine National Park are still very poor, with people living in remote areas with little to no resources. A herd of elephant or buffalo moving through a village can have a devastating effect on people’s livelihoods,” says Ernst.

The Banhine ranger team is often called upon by park management or community members to assist with human-wildlife conflict mitigation, typically directing herds away from crops or human settlements. The team also educates community members on safe ways to deter wildlife without causing them any harm.

Securing the park

In 2019, the anti-poaching team consisting of 32 well-trained men and women spent over 4 000 hours on patrol. They removed almost 700 snares from the system and made 14 arrests. Ernst says, “patrolling in this hot and dry landscape will challenge any ranger and the dedication of the Banhine rangers is admirable. They are very motivated, dedicated and disciplined, which can be seen by the good results the rangers achieved to date.”

To improve communication in the park, the radio network was recently upgraded. “Connectivity now secured throughout the Park not only improves effectivity in patrol management but it also improves the operational safety of field rangers,” says Ernst.

An infrastructure development project also saw the construction of a new house for the anti-poaching manager, as well as existing field ranger pickets upgraded. “Moving from a tent in which I lived for two years and sometimes shared with the odd snake and other creatures into a newly constructed house has made life in Banhine easier,” admits Ernst.

“Our initial focus has been on strengthening the park’s operational foundation through improved communications, infrastructure and mobility, while also learning more about the landscape through protection operations. Through this we have learnt the critical importance water plays for wildlife, park and communities and this now forms the basis of future plans for community development support and wildlife relocations,” says Antony.

A remarkable discovery

Ernst deploys camera traps throughout the park at various water holes and game paths and says that they provide a wealth of knowledge. “A highlight for me was sifting through hundreds of photos, only to suddenly come across a leopard in one of the photos. It was amazing to see the large spotted cat walking across the frames as it was the first time in more than two decades that a leopard had been photographed in Banhine.” Another surprise was a brown hyaena recently identified in a camera trap, as the park is a significant distance eastwards of the reported range of this seldom-seen hyaena.

The Park Warden of Banhine, Abel Nhabanga, says, “The improvement in living and working conditions, as well as the employment of additional rangers, has contributed to enhanced protection services, not only to secure wildlife but also in preventing illegal charcoaling and logging. It has been pleasing to see the annual growth in wildlife numbers. There still remains a long way to go in terms of more community support programmes and the reintroduction of certain species which were historically found in the park.”

In July 2018, Peace Parks Foundation and Mozambique’s National Administration for Conservation Areas (ANAC) formalised their long-standing alliance in developing Banhine National Park with the signing of a formal partnership agreement. Projects are focused on strengthening anti-poaching activities, rewilding to restore balance to the ecosystem and boost tourism offering, and improving the livelihoods of communities in and around the park.

Looking to the future, Antony says, “by securing additional funding, we will be able to provide water resources to the surrounding communities as well as animals living in the park. We will also rewild Banhine by bringing back historic species, ensuring their safety with effective anti-poaching measures. Through this, Banhine will have a sustainable and attractive wildlife product to offer tourists, as well as function as a critical link in the connectivity chain between the various Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area national parks.”